Please note: The essay published here is only a short excerpt of my 120-page master’s thesis. The topic of the master’s thesis is: “Conceptual design of an onboarding program for temporary workers”. The master’s thesis received the highest grade of 1.0 and also received a letter of recommendation.

If you would like to receive further information on this important topic, I look forward to hearing from you!

The employment form of temporary workers is an important component to ensure the flexibility and profitability of a country. However, the topic of induction of temporary workers in user companies has not been sufficiently addressed in research, nor in practice. Therefore, this master’s thesis aims to design an onboarding guide specifically for temporary workers that can be implemented by user companies, taking into account the cost and time factors. In order to be able to sufficiently investigate the topic, qualitative expert interviews were conducted with various representatives* who are directly involved in the onboarding process of temporary workers. Based on their statements, an onboarding program was conceptualized that can be implemented by user companies in a cost- and time-saving manner. To illustrate the topic, various components of such an onboarding program were created as examples.

Due to the increasing demand of companies for flexible personnel solutions, the share of temporary workers in departments is steadily increasing. In 2015, this form of employment reached its highest level to date with 951,000 temporary workers (Bundesagentur für Arbeit, 2016). Permanent cost and time pressure is prompting companies to deploy personnel quickly and flexibly. However, the topic of onboarding temporary workers has not received sufficient attention in research, nor in practice.

This introductory chapter begins by delineating the content and defining the basic terms. Then, within the theoretical-conceptual framework, the rights and obligations of the parties involved are examined in order to understand the employment model of employee leasing and to know the responsibilities of the actors. This theoretical construct thus provides the basis of the induction plan for temporary workers.

Chapter three presents and explains the chosen research method. In doing so, the quality criteria and principles of qualitative research are discussed in more detail. This chapter also explains how the interviews were conducted, as well as their subsequent data analysis according to Mayring (2002).

The fourth chapter summarizes the results from the interviews. The focus is on surprising findings and statements from the experts that are useful for the onboarding program.

In the fifth chapter, the onboarding concept for temporary workers is distinguished from a “classic” onboarding program for future permanent employees. Subsequently, the onboarding program is presented as an example from the conception phase to the end of the assignment of the temporary workers. The difficulties that can arise during the creation and implementation of such a concept are also dealt with in this chapter. Finally, recommendations for action for user companies are presented, which emerged from the discussions with the experts.

The sixth and final chapter summarizes the results of this study and provides an outlook on future developments for the induction of temporary workers.

Definition and conceptual delimitation

For the successful conceptual design and implementation of an onboarding concept for temporary workers, a comprehensive examination of the topic of employee leasing (ANÜ) is necessary. To this end, the fundamental terms must first be differentiated from one another and their use explained in the theoretical context.

1.1.1 Employee leasing

The commercial hiring out of workers has many names in business practice. Thus, the terms range from ANÜ to personnel leasing to temporary work to agency work (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013; Ulber, 2015). Often, these terms are used synonymously in their meaning, but not in their interpretation. While acting temporary employment agencies try to establish the term temporary work, trade unions deliberately use the term temporary work as well as temporary agency workers. The goal of the actors here is to assign a certain positive or negative interpretation to this work model with the help of the connotation of the terms (Gutmann & Kilian).

The term “temporary employment”, which is consistently used by trade unions, is aimed at the definition of the term “loan” (Haldenwang, 2008), according to which, under Section 589 of the German Civil Code, a commodity is loaned to a third party free of charge. Although this does not apply to ANÜ, the term “temporary employment” has nevertheless become widely established in German usage and is used in the German Temporary Employment Act (AÜG) to the extent that the actors involved are referred to as temporary workers, as the operating company and as the lender.

The hiring companies, on the other hand, try to establish the neutral term of temporary employment. The reason given for this usage is that it is a coherent translation of the internationally used term of “temporary work” (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013). Parallel to the expression of temporary work, the hiring companies therefore refer to their employees as temporary workers (Schwaab, 2009).

The form of employment itself is referred to as ANÜ in the AÜG. Although the AÜG does not contain a concrete definition of the term ANÜ, Section 1 (1) sentences 1 and 2 AÜG provides a description of the process of AÜN: “Employers who, as lenders, wish to provide third parties (Einsatzbetrieb n) with employees (temporary workers) for the performance of work as part of their economic activity require permission. The transfer of employees to the company of assignment is temporary [emphasis added by the author].”

Since this paragraph led to uncertainties in operational practice, it was concretized by the Federal Labor Court. Thus, according to the case law of the Federal Labor Court of 03.12.1997, ANÜ exists if an employer makes his employees available to third parties, on the basis of an agreement, according to which the user company can use these employees as if they were its own personnel (Pollert, 2011). Another characteristic of this process is that the assignment must be temporary. However, the law does not provide any information at this point on how the term temporary is defined. In the past, this legal gray area led to great uncertainty both on the part of the temporary employment agency and especially on the part of the user company, since the works council can refuse its consent to the use of LAK if the assignment is longer than temporary. According to current case law of the Federal Labor Court, a temporary assignment is understood to mean that the assignment must be “limited in time in advance” (Bundesarbeitsgericht, 2013). Accordingly, this term has not been fixed to a temporal dimension so far and LACs can be employed by a user enterprise for several years without violating the temporary nature of ANÜ (Pollert, 2011). However, this problem is to be solved with the new draft law of the Federal Government as of 01 January 2017. With the amendment of the AÜG, the maximum assignment period of LAC at the same user company is to be limited to 18 months (Bundesregierung, 2016). Exceptions are still possible through company agreements or collective bargaining clauses, but only up to a maximum duration of 24 months (Bundesregierung, 2016). On the basis of the explanations presented, the term ANÜ is used below to describe this employment model, in accordance with §1 para.1 sentences 1 and 2 AÜG.

In addition to the definition of ANÜ, a distinction must also be made between commercial ANÜ, the so-called non-genuine ANÜ, and genuine ANÜ, the occasional ANÜ. The term “commercial temporary employment agency” describes a process whereby an employer “hires out” employees to another company in return for remuneration. The focus here is on the intention to make a profit (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013). This means that the purpose of ANÜ is for the hiring company to achieve a monetary benefit, which can also take the form of competitive advantages (Pollert, 2011). Since the laws of the AÜG exclusively regulate the use of non-genuine ANÜ and the expert interviews conducted in this thesis are all related to commercial ANÜ, the term ANÜ will be used synonymously with commercial hiring out in the following.

Against the backdrop of a wide range of employment opportunities, ANÜ is just one of many options that enable employees to integrate the factor of work into their lives on an individual basis. In Germany, these different work models are divided into typical and atypical forms of employment (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2010). Accordingly, a typical form of employment is understood to be the so-called normal employment relationship, while atypical employment deviates from this employment relationship. The normal employment relationship is characterized by fixed criteria such as permanent and unlimited full-time employment, the possibility of collective representation of interests through works councils and trade unions, and a regular living wage, including integration into the statutory social security system (Oschmiansky, Kühl & Obermeier, 2014).

Consequently, all employees who, due to their employment relationship, have no possibility of being collectively represented, but also employees who are not employed for an indefinite period of time or who work 20 hours or less per week, are automatically assigned to an atypical form of employment. Moreover, the Federal Statistical Office explicitly excludes LAC from a normal employment relationship in its definition, since “A normal employee […] works directly in the company with which he or she has an employment contract. This is not the case for temporary workers who are lent out to other companies by their employer — the temporary employment agency.” (Federal Statistical Office, 2015). Accordingly, in addition to ANÜ, temporary employment relationships, part-time work and undeclared work, among others, are also classified as atypical employment relationships. In this way, legal employment relationships are placed on an equal footing with illegal forms of employment such as undeclared work. Although the Federal Statistical Office (2010) also makes it clear that atypical employment can be deliberately chosen in order to better reconcile personal and professional requirements, it also points out that atypical employment relationships often cannot meet the requirement of being able to finance the livelihood of employees (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2010).

The fact that such a distinction between normal employment relationships and atypical employment is no longer appropriate and needs to be redefined becomes clear when looking at current statistics, as shown in table 1.

Table 1

Share of atypical employment in total employment.

Notes. Own presentation based on: Federal Statistical Office (2016) at: https://www.destatis.de/DE/ZahlenFakten/GesamtwirtschaftUmwelt/Arbeitsmarkt/Erwerbstaetigkeit/TabellenArbeitskraefteerhebung/AtypKernerwerbErwerbsformZR.html.

According to a study conducted by the Hans Böckler Foundation in 2015, the ratio of atypical employees was as high as 39% in 2015, with 14,126 people (Hans Böckler Foundation, 2015). This means that almost every fourth employee has an atypical employment relationship. Part-time work and temporary work have shown particular growth. These differences in the statistics are due to differences in data collection. While the Federal Statistical Office only considers working hours of less than 21 hours as part-time employment, the Hans Böckler Foundation already classifies every shorter working week as part-time compared to full-time employees (Hans Böckler Foundation, 2015).

Despite the discrepancies in the recording of atypical employment relationships, a long-term increase in this form of employment cannot be denied. In a world that is in a state of permanent change, which also affects employment, the question arises as to what extent the so-called normal employment relationship really still represents the norm today. Current studies show that especially the flexible components of work, such as changing work locations, performance-linked remuneration systems and changing work tasks, in the sense of so-called upward mobility, tend to increase strongly (Minssen, 2012). However, it is not only work as such that is becoming increasingly flexible; employees themselves are also contributing to this development by specifically demanding employment relationships that allow them a great deal of freedom in shaping their work (Federal Ministry for Family Affairs, Women, Senior Citizens and Youth, 2015; Institut für Demoskopie Allensbach, 2013).

1.1.1 Actors in the Temporary Employment Business

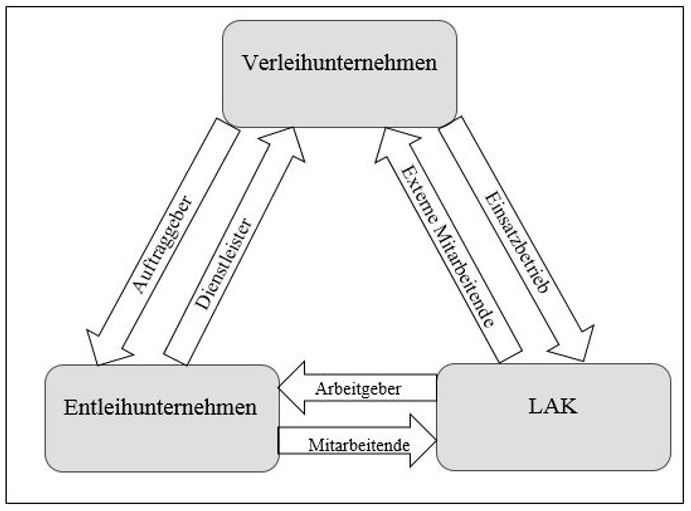

Characteristic for ANÜ are not only the contractual relations between the actors, but also the subject of the contract itself. Accordingly, in the case of ANÜ, the LAK, or their labor, are the subject of the contract (Lindner-Lohmann, Lohmann & Schirmer, 2012). Due to these particularities, there is also no uniform use of terms for the actors within ANÜ. Rather, the perspective of the respective parties involved determines the term used, as can be seen in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1: Perspective terminology in ANÜ

(Source: Own representation based on: Gutmann, J. & Kilian, S., 2013, p.165).

Accordingly, from the perspective of the temporary employment agencies, the LAK are their own employees who perform their work at the user company. The user company, on the other hand, is the customer that requests the required human resources from the temporary employment agency. The company that provides personnel, on the other hand, calls itself a temporary employment agency.

For the LAK, meanwhile, the picture is different. For them, the temporary employment agency is the employer, but the user company is the company where the work is performed. Whether LACs feel more like employees of the temporary employment agency or of the user company differs from LAC to LAC (Thiel, 2016). The decisive factor here is not only the esteem in which the LAC is held, but also the motive for pursuing employment in the temporary employment agency. After all, if employees have consciously chosen this type of employment, they are more likely to feel that they belong to the temporary employment agency, as this form of employment fits better with their life plan (Härtl, 2016). However, if they would like to use ANÜ in order to obtain a permanent position in a specific hirer company, then they are more likely to feel that they belong to the user company, as in this case ANÜ is only the means to an end (Breitscheidel, 2010). Chapter 5.5.1 “Commitment dilemma” takes a closer look at this problem.

From the perspective of the user company, the temporary employment agency is the personnel service provider that supplies the right personnel at the right time in the required numbers. The LAC, on the other hand, are the external employees for the user company (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013).

Since the present work is based on the applicable legal provisions and does not represent a political positioning, neither on the union side nor on the employee leasing side, the use of terminology for the parties involved according to the AÜG will follow. In the following, companies that use ANÜ for personnel flexibilization are therefore referred to as user companies. Parallel to this, the employees who work within the framework of ANÜ are referred to as LAK. Consequently, companies that offer temporary employment services should be referred to as hiring companies. In order to avoid confusion, however, these companies are referred to below as temporary employment agencies.

1.1.2 The concept of onboarding

In the literature, the term onboarding is not used selectively (Feldman, 1981). Thus, onboarding is understood by some authors as synonymous with the term integration (Schmidt, 2014) as well as with induction (Brenner & Brenner, 2001). Therefore, the terms onboarding, induction as well as integration are also used synonymously in this paper. However, the implementation of integration measures is not limited to the work area of the new employees. Rather, onboarding must be understood as a holistic process that takes place in parallel at several corporate levels (Engelhardt, 2006). Accordingly, the business areas involved include not only the human resources department but also the management (Lohaus & Habermann, 2015), as well as the respective manager and the new employee’s direct colleagues (Dravoj, 2016). Within the onboarding process, a distinction is also made between professional and social integration (Blum, 2010). While the focus of professional integration is on learning the work task and the knowledge required for it, the goal of social integration is the acceptance into the team as well as the adoption of the corporate culture (Becker, 2013). However, although the company’s efforts are crucial for the success of onboarding (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013), the employees themselves are also responsible for the success of their onboarding. This is because, in addition to the technical qualifications of the new employees, their cognitive as well as emotional abilities also determine the successful course of the onboarding program (Brenner & Brenner, 2001).

The socialization of future employees plays a central role here. In this context, socialization means the adaptation to certain processes and activities, but also the alignment of expectations (Lohaus & Habermann, 2015). In addition to pre-socialization, anticipatory socialization is also crucial for successful onboarding. This term covers all experiences that are decisive for the development of personal values and norms (Engelhardt, 2006). Early experiences that took place in the person’s immediate environment are particularly formative. Based on these experiences, not only are values and norms formed, but the person’s personality is defined by the situations experienced, which is expressed in language, manners, and habits, among other things (Neuberger, 1991).

This type of socialization describes the period before entering an organization up to the first day on the job (Feldman, 1981; Neuberger, 1991). Based on pre-existing value patterns, certain expectations about future employment develop during the pre-entry period. This “pre-entry phase” involves the alignment of one’s values with those of the organization. Although there is only sporadic contact between the future employees and the company in this phase, this is perceived and evaluated particularly intensively on the part of the employees, since they do not yet have any other information with which their own values can be compared. If the company’s values do not match those of the future employees or if the company does not behave in accordance with their expectations, successful induction is jeopardized (Engelhardt, 2006). This knowledge is of enormous importance, especially for the creation of an onboarding guide, since the foundation for a successful integration is already laid here (Engelhardt). The knowledge of anticipatory socialization should therefore be used to positively influence integration.

The goal of a successful onboarding concept is the full integration of new employees. In this process, the new employees are to be transformed from so-called company externals to company internals (Bauer, Bodner, Erdogan, Truxillo & Tucker, 2007). This so-called “metamorphosis phase” (Noe, Hollenbeck, Gerhart & Wright, 2012) is considered complete when new employees are integrated to such an extent that they are no longer recognized as such. Consequently, onboarding can only be purposeful if both the new employees and the organization want the onboarding to take place in the first place (Becker, 2013). In the following, therefore, the term onboarding is understood in this master thesis as a systematic process (Becker, 2013) that enables employees to work successfully in the new organization (Bauer & Erdogan, 2011) and also makes them feel welcome (Watzka, 2014).

Contractual rights and obligations of the parties involved

1.1.3 Triangular relationship

As has already been presented, an ANÜ exists when an employer temporarily hires out its employees to third parties (Ulber, 2015). Due to the special contractual constellation, there are overlaps in the areas of responsibility, which often leads to problems in operational practice (Böhm, Henning & Popp, 2013; Gutmann & Kilian, 2013). Subsequently, the contractual relationships within the triangular relationship, as well as the associated rights and obligations between the actors, will therefore be explained.

The prerequisite of the triangular relationship is the written contract between the temporary employment agency and the user company as required by §12 AÜG (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013). The scope of the right to issue instructions to the user company is derived from this so-called employee leasing contract. Although LACs contribute their labor within the user company, there are no contractual relationships between these two actors, but there are mutual rights and obligations (Ulber, 2015). Accordingly, the company of assignment, i.e. the user company, is obligated to the LAC in the area of occupational health and safety pursuant to Section 11 (6) Sentence 1 AÜG to the extent that their activities are subject to the statutory occupational health and safety regulations applicable in the user company. The duty of care, on the other hand, remains with the temporary employment agency, even if the LAK do not perform their work in its company organization (Ulber). Direct employment contract relationships thus arise only from the employment relationship between the LAK and the temporary employment agency, i.e. the direct employer (Ulber). This employment contract gives rise to mutual claims and obligations between the parties to the contract.

Due to this special situation, which effectively confronts the LAK with two employers, it is necessary for the right to issue instructions to be split between the temporary employment agency and the user company. In the case of a temporary employment agency, this is done by transferring the right of direction from the temporary employment agency to the user company. It should be noted, however, that in accordance with Section 613 sentence 2 of the German Civil Code (BGB), such a transfer of the right of direction to a third party is only valid with the prior consent of the employee. The employment contract signed by the employee with the temporary employment agency is regarded as consent (Pollert, 2011). On the basis of this contractual relationship, employment contract rights and obligations arise only between the temporary employment agency and the LAC. However, due to the transfer of the right to issue instructions, the user company, as the de facto employer, also has management rights in connection with the performance of the activity (Ulber, 2015). However, the right of direction of the user company only extends to the activities specified in the employee leasing contract, to the duration of the working hours and to the place of work (Pollert; Ulber). For all other areas of activity, the sole right of direction remains with the temporary employment agency (Pollert).

This entails some consequences under labor law that differ from the regular employer-employee relationship. Although the employees are employees of the temporary employment agency on the basis of their employment contract with the agency, they perform their work in a different company, namely in the user company. Due to this special situation, some difficulties arise in the implementation of the employment contract obligations. In addition to organizational hurdles on the part of the hiring company, such as the risk assessment of the workplace, there are also social problems. Constantly changing assignment companies (Bornewasser, 2013; Schröder, 2010) require LAC to permanently adapt to their new colleagues, as well as to the respective work task (Breitscheidel, 2010; Schröder, 2010). In addition to this burden, there is also repeated social exclusion of LACs on the part of the core workforce (Bolder, Naevecke & Schulte, 2005; Breitscheidel, 2010; Thiel, 2016).

Although a large number of equality measures have already been created with the help of §13 b AÜG, there are still major deficits in the implementation of comprehensive and, above all, social inclusion (Breitscheidel, 2010). In order to understand the problem of the often lacking integration of LAC, it is necessary to know the respective responsibilities, rights and duties of all parties involved.

1.1.4 Rights and duties of temporary employment agencies

Temporary employment agencies occupy a key position in ANÜ due to the triangular relationship. As an employer for LAK on the one hand and as a service provider for the hirer on the other, they represent an interface in this contractual relationship and must fulfill the duties of a service provider in addition to the employer duties (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013).

Since temporary employment agencies act as contractual employers for the LAC, they are responsible for complying with general employer obligations, such as paying remuneration, approving leave, and the obligation to provide references (Ulber, 2015). The fact that the employees do not perform their services in the operational organization of the de facto employer is irrelevant (Ulber). Since the focus of this master’s thesis is on the specifics of the employer’s contractual obligations in the context of temporary employment, the general employer obligations, such as the obligation to pay wages and provide references, will not be discussed in detail here. Instead, the special features of the employment contract obligations in the context of temporary employment agencies will be elaborated and presented.

Since temporary employment agencies have no direct influence on the prevailing conditions in the operational organization of the assignment company, they are obliged to carry out an assessment of the workplace in order to comply with Section 5 (1) of the Occupational Health and Safety Act (ArbSchG). To this end, the place of deployment of the LAK must be checked for possible hazards and, in accordance with Section 12 (2) of the ArbSchG, appropriate safety instruction must be provided. In addition, personal protective equipment is usually provided by the temporary employment agency (Thiel, 2016), unless otherwise agreed in the temporary employment contract (Dreyer, 2009). The fact that the companies in which temporary workers are deployed frequently change within a short period of time (Schäfer, 2009) and, as a result, the activities change, is a special feature of temporary employment agencies that must be taken into account. In addition to the safety instructions, the so-called basic examinations must also be continually adapted to the employees’ new workplaces in accordance with § 3 of the Ordinance on Occupational Health Precautions. However, the user company is also responsible for the occupational safety of the LAK. Section 11 (6) of the German Temporary Employment Act (AÜG) stipulates that LAK must be informed and instructed by the user company about hazards arising from their area of work. Despite this supplementary regulation, the majority of responsibility for occupational health and safety remains with the temporary employment agency. In conclusion, it can be said that the temporary employment agency’s occupational health and safety obligations differ only slightly from the regular employer obligations of a normal employment relationship. Nevertheless, there is an increased potential for danger in this form of employment because the responsibilities between the two companies are not clearly defined. Therefore, the legislator has provided for mutual responsibility in the area of occupational health and safety, as well as the mandatory nature of these duties on the part of the temporary employment agency. The mandatory nature of the duties of care is regulated in Section 619 of the German Civil Code (BGB). This means that temporary employment agencies have no possibility of transferring the duty of care, even partially, to the user company. The temporary employment agency’s compliance with the duty of care is therefore a special feature of temporary employment agencies, as it is required to fulfill the same duties as an employer for its permanent workforce.

In addition to the duty of care, the temporary employment agency also bears the employer risk in accordance with Section 1 (2) AÜG. The decisive factor in the allocation of employer risk is which contractual partner assumes the risk of compensating the LAK during non-assignment periods (Pollert, 2011). This function is particularly important in ANÜ (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013), because temporary employment agencies, as suppliers of personnel, are only informed very late about crucial decisions of the user companies. Often, only the information on whether to increase or decrease staff is passed on to the temporary employment agencies. As a result, fluctuations in orders are experienced as extremely short-term, which enormously limits the options for responding to this situation with suitable working time models. For this reason, staffing agencies are dependent on the user companies and have only minimal leeway to respond to the current order situation (Schröder, 2010). This so-called “bullwhip effect” (Lee, Padmanabhan & Whang, 1997) means that temporary staffing firms are subject to very dynamic order planning. In order to nevertheless fulfill the orders in the best possible way, they make extensive use of created personnel pools, as well as the instrument of working time accounts (Breitscheidel, 2010). However, flexible staff planning cannot always compensate for the fluctuations of the user companies. Often, LACs are canceled by the hiring company at short notice, or a planned assignment of several months is terminated after only a few days (Breitscheidel). The risk of this high degree of flexibility is borne by the temporary employment agency. Due to the employer’s risk, it is obliged to find a new assignment for the LAK in accordance with the activities specified in the employment contract. If this is not successful, the hiring company is obliged to compensate the LAK for the time they are not deployed (Pollert, 2011). Following a ruling by the Berlin-Brandenburg Regional Labor Court, the previously common practice of offsetting the minus hours resulting from non-operational time against the LAK’s plus hours was deemed inadmissible (Haufe Online Redaktion, 2015; Schröder, 2010). Such an approach would shift the entrepreneurial risk to the LAK (Landesarbeitsgericht Berlin-Brandenburg, 2014; Schröder). Thus, the employer risk therefore has a special significance in ANÜ. In addition to the employer risk, the temporary employment agency also has the obligation under Section 11 (2) AÜG to hand over a leaflet from the Employment Agency upon conclusion of the contract. This leaflet summarizes the rights and obligations of those involved in temporary employment.

Finally, equal treatment in accordance with Section 75 (1) of the Works Constitution Act (BetrVG) must be mentioned, which grants every employee the right to equal treatment. This principle is much more difficult to implement in temporary employment than in other forms of employment. The constantly changing locations where LAC are deployed (Breitscheidel, 2010; Schäfer, 2009), as well as the associated changing activities, make equal treatment difficult not only in the user company, but also within the temporary employment agency. This is because it is not always easy to comply with the principle of equal treatment due to the dynamic deployment of personnel (Thiel, 2016; Ulber, 2015). Thus, the permanently one-sided allocation of certain assignments to selected groups of employees also leads to discrimination against employees. For example, LAC who have a car tend to be loaned out to far-away client companies more often than is the case with non-motorized employees (Breitscheidel, 2010). In parallel with this approach, the performance of one-sided activities, e.g. heavy physical work, is often distributed unilaterally among employees (Ulber, 2015). As a result, these LAC are often exposed to a constantly higher load than their colleagues over a long period of time. This is unequal treatment according to § 75 para.1 BetrVG. However, it is not only the treatment in the rental companies that poses a problem. The equal treatment of LAC in user companies also repeatedly comes up against limits. Since the dispatchers of the temporary employment agencies cannot be constantly on site with the deployed LAK (Thiel, 2016), difficulties arise in monitoring the implementation of equal treatment. If the affected LACs themselves do not report problems in the hirer company, it is very difficult for the personnel dispatchers to recognize unequal treatment and take timely countermeasures, since they are not regularly, or in some cases not even, on site (Thiel, 2016).

However, temporary employment agencies do not only have duties to fulfill towards the LAC. As a service provider, the company also has obligations to its customers. The main obligation here lies in the provision of labor. The special feature of this supplier relationship is characterized by the “supplied product”, namely the employees. Thus, the requirements that the customer places on the personnel service provider differ enormously from those of a product supplier. On the basis of the temporary employment contract, the temporary employment agency undertakes to make its employees available to the user company. As a rule, the subject of the contract is not a specific employee. Instead, the requirements that the LAC must fulfill are specified (Pollert, 2011). However, although the required qualifications are clearly defined in the temporary employment contracts, each person performs the tasks assigned to him or her differently. This results in the core problem of temporary employment: people are ordered and delivered like goods (Breitscheidel, 2010). The user companies expect the LAK, who come to replace a regular employee who has dropped out, to do the work exactly as their predecessors did (Thiel, 2016). Accordingly, the temporary employment agency is obliged to provide replacement services if the LAK do not perform identically. It is irrelevant whether it is responsible for the reason for the non-performance (Pollert, 2011). It should be emphasized, however, that the temporary employment agency can be held liable for the so-called “poor performance”, but only within the scope of the professional and personal suitability of the LAK provided. However, the temporary employment agency cannot be held liable for the performance of the work as such (Gutmann & Kilian, 2013).

In addition, the temporary employment agency is also obliged to comply with certain notification and reporting obligations vis-à-vis the user company. Accordingly, the temporary employment agency must inform the user company immediately if the permit for commercial temporary employment loses its validity, e.g. through withdrawal or non-renewal (Pollert, 2011).

In addition to the aforementioned obligations, temporary employment agencies also have rights, such as the right to give instructions to their employees. Since this right of direction is split between the temporary employment agency and the hirer in ANÜ, the right of direction of the hirer is always subject to the original right of direction of the temporary employment agency (Ulber, 2015). Accordingly, the temporary employment agency has a superior right to issue instructions to the LAC. Further rights arise from the contractual relationship with the assignment company. If, for example, the assignment company is in arrears with payments, the temporary employment agency has a right of retention (Pollert, 2011). This is expressed in the withholding of the LAK. However, it should be noted that in this case the LAK do not work, but costs are still incurred by the temporary employment agency due to the continued payment of wages (Pollert). Furthermore, the customer can request the required LAK from another temporary employment agency at any time. Thus, the right of retention only has a minor effect in the ANÜ. Another right of the temporary employment agency is the premature termination of the employee leasing contract. The prerequisite for this is the sustained non-fulfillment of obligations on the part of the temporary employment agency. In conclusion, it can be said that the temporary employment agency has extensive obligations, while its rights vis-à-vis the hirer arise primarily from the hirer’s failure to comply with the contracts concluded.

- End of the excerpt of the master thesis -.

*For reasons of better readability, the simultaneous use of the language forms male, female and diverse (m/f/d) is omitted in the web version. All personal designations apply equally to all genders.